I was raped by ranger from Harry’s Africa charity as I held on to my baby: The full harrowing details of rainforest families’ claims of torture – as revealed by IAN BIRRELL in video dispatch from the Congo jungle

The excited family set off to forage for one of their favourite foods: the luscious yellow honey considered beneficial for children’s health that is found amid the dense foliage and towering trees deep inside the spectacular Congo rainforest.

Instead, they became trapped in a horror story as guards working for the African Parks conservation charity spotted the father high up a tree collecting lumps of honeycomb from a bees’ nest, with his wife and seven children waiting patiently below.

‘After coming down the tree, I was arrested and handcuffed,’ claims Justin Zoa. The six guards ordered the family not to leave the area. Then, after a fretful night in the dark forest, he says the torture started.

‘They removed the handcuffs, then took off my clothes,’ said Justin, one of the Baka indigenous people once known as pygmies. ‘Then they lit candles, dripping the wax on to my back, before taking off their belts and whipping me on the same part of my back. I was very scared. I thought I would die, and seeing my wife and children crying made it even more painful.’

Justin has no idea how long the beating and brutality lasted. But eventually the thugs in uniform left him with his distraught family so they could return home.

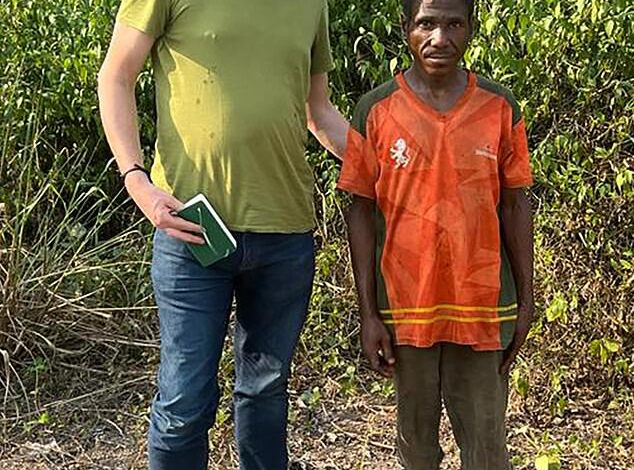

Ian Birrell with Justin Zoa, who told of being brutally whipped

Prince Harry was the charity’s president for six years until being elevated to the governing board of directors

This was just one allegation against the armed militia run by African Parks, the fast-expanding charity which Prince Harry helps lead as a member of the board of directors, and which manages 22 protected areas covering 57,000 square miles in 12 countries.

I have spent several days investigating in this remote region, an extraordinary place of tropical beauty in the northern part of the Republic of the Congo, and I heard appalling stories of brutality, rape and torture involving this conservation militia.

The story epitomises the problems that arise when conservation groups move in to protect wildlife on land that indigenous people have occupied for millennia.

Such is the climate of fear that some were terrified as they detailed the abuse. ‘Many people are scared to talk,’ said a community leader.

Similar allegations have been highlighted by human rights groups such as Survival International for a decade.

Justin had committed no offence. His family was inside one of Africa’s oldest national parks where the law – according to a man who served as the area’s most senior government official – only prohibits killing of protected species such as gorillas, chimpanzees and the elusive forest elephants, so still allows locals to enter the forest, forage or even hunt small animals.

However, the laws do not seem to prevent barbaric treatment of human beings.

Odzala-Kokoua National Park is home to more than 400 bird species, 110 types of mammal and at least 4,400 plant varieties

Justin’s wounds healed with the help of traditional forest medicines, though the scars are still visible and his psychological anguish intense. ‘I was doing nothing bad, nothing illegal, but it’s caused such damage to my mind. Often it comes back suddenly.’

Since that dark day, he’s not been back in the forest, his children no longer enjoy honey and he ekes out a tough existence trapping birds and relying on a small plot of bananas and cocoa to feed his family. ‘Life is very hard,’ says Justin.

Other villagers do not dare go into the bountiful forest that has traditionally sustained the Baka, whose knowledge of flora and fauna in the world’s second biggest rainforest is unmatched.

I met Justin inside Odzala-Kokoua National Park, a protected region larger than Yorkshire. It was created almost a century ago and is home to more than 400 bird species, 110 types of mammal and at least 4,400 plant varieties.

African Parks signed a 25-year deal to run this lightly-populated area in 2010. The charity has expanded fast as cash-strapped governments outsource the running of their parks.

As I entered the protected area, three guards, chatting in the shade with a rifle propped beside them, told me they were trained by soldiers – reportedly French, Israeli and South African veterans – and paid by African Parks. One showed me the charity’s logo on the sleeve of his T-shirt, worn under a military-style uniform.

In village after village, I heard disturbing stories of Baka people too fearful to enter their forests after threats, violence and warnings to keep out from this militia – although tourists willing to pay almost £10,000 can fly by private plane from the capital Brazzaville to spend a week in luxury lodges and watch gorillas.

An African Parks source said the management plan at Odzala ‘entrenched rights of abode and use of natural resources by local communities subject to limits on which species could be hunted, the areas where it could take place and the types of weapon permitted.’

But Medard Mossendjo, a father of two from the village of Biessi, said many Baka were scared to enter the forest. ‘You pick a vegetable and the guards say it is food for an animal, so they beat you.’

He claims he and his wife were assaulted by five African Parks guards while hunting. ‘They beat us both hard – slapping and punching us.’

Afterwards, he said the rangers put him in prison in a town about two hours away and detained him for eight months, during which time his health and weight declined alarmingly as he went hungry and thirsty. ‘I was in such a bad state, about to die,’ he said.

One man in the village of Sembe claimed he was tied up and beaten with sticks when collecting wood because elephants, which might want to eat the twigs and branches, took priority.

He said chillingly: ‘They’re killing us slowly anyway. We’re suffering so much that we might as well be dead. I’m thinking of taking poison with my wife and children.’

A Baka community leader claimed another man died a week after being assaulted and jailed with his injuries left untreated – then his wife died three weeks later, leaving five children as orphans. He told me of a second victim shot in the arm four years ago after trying to hide from a patrol in the undergrowth.

Lobila Gaston, also from Sembe, claimed four guards beat him and his younger brother with a barrage of punches, kicks and sticks as he returned from an officially licensed trip hunting gazelle.

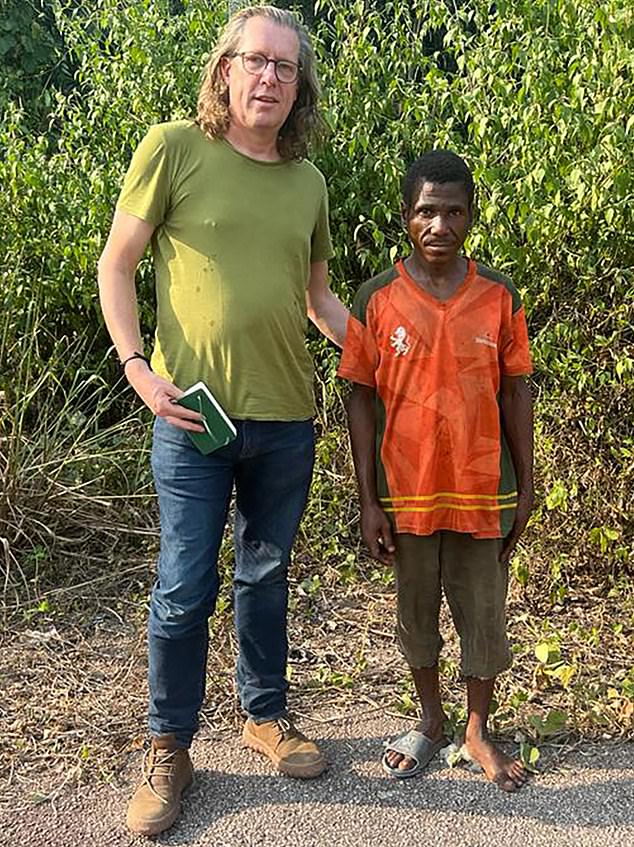

Reporter Ian Birrell with two Baka men who say they were beaten

Odzala-Kokoua National Park is home to more than 400 bird species, 110 types of mammal and at least 4,400 plant varieties

‘The beating lasted long enough for me to lose consciousness. They must have stopped after I passed out. I got beaten mostly on the head and face. When I came back to my village, people could hardly recognise me with all the blood,’ he said. ‘My little brother did not survive. He went to hospital and died.’

Little wonder that this man in his late forties, like others brave enough to talk, said he hates the conservation group and blames it for destroying their traditional way of life. ‘The past was far better for us – and the reason is all down to African Parks,’ he said sadly.

Such stories could not be further from the slick promotional claims of the charity, which launched in 2000 with backing from a Dutch billionaire and bold talk of adopting a business approach to conservation and alleviating poverty ‘in partnership with governments and local communities’.

Peter Fearnhead, the chief executive who was a guest at Prince Harry’s wedding, told The Economist that his model relied on a clear government mandate, sound management and cash from donors such as the EU and the American development agency USAID.

The charity’s biggest private donor is Hansjorg Wyss, a Swiss billionaire and part of the consortium that owns Chelsea Football Club, who has given $1billon (£800 million) to conservation causes. The People’s Postcode Lottery, based in Edinburgh, has handed African Parks £8.2 million since 2015.

The charity says that within five years of taking over a park, it reduces poaching by 70 per cent on average and boosts wildlife numbers by 50 per cent. Yet like other conservation bodies – most notably the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) – it has faced persistent accusations about the armed militia empowered to trample over the human rights of indigenous people in the name of protecting wildlife.

Survival International first raised the issues with an African Parks official in 2013.

In a meeting the following year, the charity’s community manager admitted problems with corruption, violence and poaching by their guards but said they needed hard evidence to act against individuals, according to the campaign group’s notes from the time. A report three years later by the group accused both African Parks and WWF of silence over human rights abuses in the Congo Basin. ‘Across the region, Baka face harassment, theft, torture and death at the hands of wildlife guards,’ it said.

One Baka activist claimed problems started with the arrival of African Parks patrols. ‘When they found people in the forest, they’d kick them out. They would beat people. After this happened one, two, three times, people do not go back into the forest.

‘They come here with their guns and weapons. They make us feel afraid and very uncomfortable. It is like an invasion.’

A doctor even claimed that armed African Parks guards would enter a local hospital ‘once or twice a week’ to stop patients discussing incidents that might damage the charity’s reputation and try to intimidate medical staff. It was common to see the guards in the hospital trying to threaten people. Even when we were writing our reports, they would lean over, not wanting us to tell the truth because it would be bad for their funders to see the cases.’

He described one case of attempted intimidation in May 2022 that involved a guard who groomed a Baka boy for paid sex. The 17-year-old had gone to hospital feeling sick and doctors found that his abuser had injured the boy’s groin and left him with a sexually transmitted infection.

It is understood the African Parks guard was sacked three months later – though he absconded before criminal charges were brought and remains on the run. Local analysts said the problems are compounded by the fact that many Bantu people – the majority of the Congo population – view the indigenous people as inferior beings, so there is widespread discrimination and forcible land-grabbing.

Sorel Eta, author of a book on forest culture, says ‘ethnocide’ is taking place. ‘Bantu people do not consider indigenous people to be human,’ he said. ‘The authorities say there are laws to protect them but the reality is very different.’

He said the forests mean everything to indigenous people. ‘They depend on it for their food, their health, even their spirituality, so if you cut them off from the forest, you kill them and their culture.’

Eta accepts that the charity protects elephants and gorillas but urged it to start a proper dialogue with indigenous people to let them back in the forest.’

It was deeply sad to meet and see these shattered indigenous communities exiled from their forests.

‘I’m really afraid of the future,’ said Moyambi Fulbert, a villager in Sembe who fled with his family from a beating with belts. ‘What African Parks is doing to the Baka people is horrible.’

I asked this passionate man what he would say to the charity’s director and former president, Prince Harry? ‘I’d tell him to stop supporting African Parks. He is a powerful man. He eats well and lives well – but we don’t have anything now and it’s all because of African Parks.

‘Maybe he doesn’t know what they are doing to our people. But if he was a good person, he’d stop the pain and suffering caused to our community.’

And he asked a simple question: ‘Where is the justice for us if everything is stopped by African Parks – even collecting honey?’

African Parks guard raped me as I held on to my baby … then I was paid £500 compensation

It was the middle of the night when the young mother was abruptly woken by someone knocking at her house. She assumed it was her husband returning from a neighbouring village – but it was a guard from the African Parks conservation charity demanding she got up immediately and followed him.

Ella Ene with son Daniel

‘The guy was wearing their uniform and had a gun,’ said Ella Ene. ‘He was threatening me, saying “I’ll shoot you” if I did not do as he said. He told me he wanted to take me to their camp.’

The mother of two says she and her fellow villagers’ movements are monitored by the guards to ensure they are in their homes at night rather than the forests, so the ranger used her husband’s absence to order her out.

She bundled up her baby Daniel – one month old and too young to leave at home – to follow the African Parks guard on the ten-minute walk to his base.

With brutal but brave honesty, she described what happened next, and how the man raped her beside the road as she clung in terror to her child. She said the guard ordered her to the ground, tore off some of her clothes and assaulted her in the pitch-black night, ignoring her screams for help and the cries of her baby.

‘I was holding my baby while being raped and trying to protect him,’ she said. ‘My first reaction had been to protect my baby. It was very violent.’

The rapist then continued escorting his agonised victim to his base, where he casually told colleagues he had brought Ella with him as her husband could not be located.

Courageously, Ella complained to his boss about the attack. As a result, she says, he decided it would be best for his guards to take her back to her village of Kokoua, where they arrived at about 4am.

Our reporter with Ella and her family

When her distraught husband Kelli Asse heard about the attack he rushed to the African Parks camp. There he says he was handcuffed and beaten about the face and body while held captive for nine hours. ‘I just wanted to see my wife,’ he said.

Ella, whose body had not recovered from giving birth at the time of the assault, said both she and her baby needed hospital treatment.

Still, almost three years after the rape, she is left in physical and mental pain, unable to forget the shocking assault and no longer able to get pregnant. She told me: ‘African Parks are very bad people. Everybody who works with them is really bad to us. That man was cruel, he was inhumane.’

She is convinced she was targeted because she is Baka, an ethnic group who live in central Africa’s rainforests. ‘We are treated like animals. Actually, animals are treated better than us because they are protected – and that is so hurtful.’

At one point as we talked, a forest guard turned up to visit the village chief and Ella looked visibly alarmed. Afterwards, she admitted: ‘I was afraid, really afraid. When I see the uniform, it’s like a trauma because I remember what happened.’

A doctor later told me African Parks guards visited the hospital after Ella had been examined and threatened staff. ‘They did not want the prosecutor to see the right reports so they came to persuade us to change them,’ he said.

According to an African Parks email I have seen, the rapist guard was dismissed after a two-month internal investigation and jailed following a court case.

Yet after just two months behind bars, he was released and put under house arrest.

A court-appointed mediator ordered a payment to Ella equivalent of about £1,300. She says she has received just £520, which a court document I have been shown states ‘was a deposit of the compensation for having been victim of an ecoguard’ and that ‘other instalments will be paid monthly’.

All the cash she has received went on medical treatment. Her husband says: ‘After the rape, the health of my wife is not good. Everything I earn goes for her health and the baby’s health.’